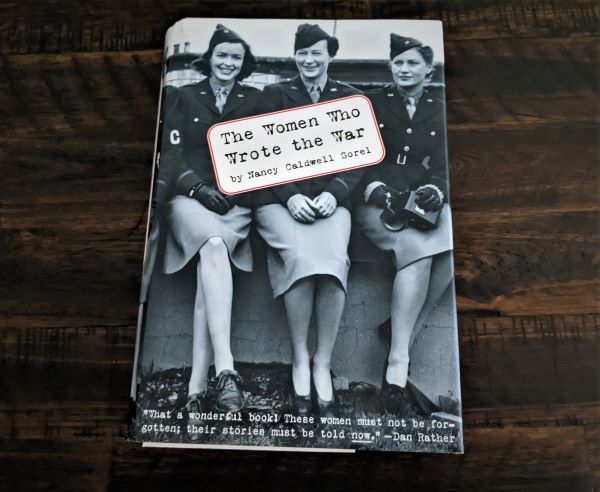

Men have thrown obstacles in the way of women in many fields for many decades, and journalism is not immune. In her book “The Women Who Wrote the War,” Nancy Caldwell Sorel describes the experiences of women who worked as correspondents during World War II.

One aspect of the style of the book that I initially found difficult was the way the narrative jumps from one journalist to another, leaving behind a mosaic of experiences that I could not in retrospect necessarily connect with the individual. Over time, though, I came to rather appreciate the approach and its demonstration of just how pervasive these women were with their work.

The obstacles were many. Publications were reluctant to hire women outside of culture and society pages. Those that did have women in harder news roles often did not employ them as foreign correspondents. The military, which had to credential those who would be working in and among troops, was slow to do so with women. And even once the reporters held the right status, the military officials tried their best to confine them to rear positions, often with nurses.

Few of their male colleagues provided any kind of warm welcome or show of respect, as they enjoyed certain professional advantages such as having their stories approved and sent back to the U.S. before the women were allowed to.

“Our presence in various fields is bitterly resented by the men we compete with,” said Peggy Hull Deull, whose experience stretched back to the first World War. “Overwhelming obstacles are frequently set up to prevent us from working.”

Photographer Dickey Chapelle used her smarts to seize the opportunity to go ashore in Okinawa, the kind of scene the author recounts over and over as women overcome and sometimes literally leap over the barriers put in their way, only to have a commander greet her with the warmest of words: “Get that broad the hell out of here!”

Despite those challenges, the women find a way to file to all kinds of publications from Life magazine to the St. Louis Post Dispatch to CBS radio. They tell stories of soldiers in hospitals, advancing through German lines and landing on beaches in France and the Pacific.

As I said there is a dizzying group of names and backstories, among them Lee Miller, Dot Avery, Iris Carpenter, Helen Kirkpatrick. But the name that stuck out again and again, and which will have me doing more reading, was Martha Gellhorn.

Gellhorn wrote for Collier’s magazine during the war, but my first notes about her come a decade earlier. Caldwell describes how in the early 1930s Gellhorn is appalled at what she finds in her work as a field investigator for the Federal Emergency Relief Administration going around the country speaking to people who have been hit by the Great Depression. Her mother is friends with Eleanor Roosevelt, and at the invitation of the president and first lady, “she moved into the White House (austerely furnished then and lacking any security)and wrote a series of stories based on her field experience.” That’s quite the work co-working space.

More than her fascinating life story, which includes being married to and eventually casting off a disappointing and annoying husband by the name of Ernest Hemingway, Gellhorn’s writing sticks out. This excerpt comes from her reporting in 1944 Italy:

“It smelled of many things, of men and dampness and old blankets and ether and pain … War, which is such a large and incomprehensible and impersonal affair, becomes very personal indeed inside a hospital, for at last it is reduced to its basic materiel, the human body. You speak to the wounded who look at you, assuming that they may want company. You try not to let your own health shout down at them; and you try to keep your face and your voice clean of pity, which nobody wants.”

This book was a very informative deep dive into a part of the war’s history that is not talked about much, and both reveals things about the conflict and the ways in which we needed, and still very much need, to do better.