Some books and their characters grab you in a way that makes you say, “Hey, that’s me! That’s my life! My experiences!” Others are a reminder that whatever proximity you may have to certain life experiences, whatever knowledge you already possess about underlying history, culture and issues, your job is to sit back and listen.

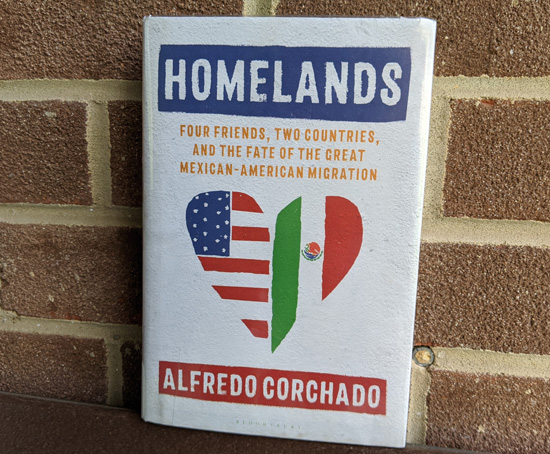

Alfredo Corchado’s “Homelands” was a “listen” book for me. He speaks of his life as a journalist that included stops in El Paso, Philadelphia and Mexico City, and the way his life changed when he connected with a fellow Mexican, quickly expanding to a circle of four, at a restaurant in Philly.

Corchado is from Durango state, and a town about two hours from where my wife is from. Seeing that immediately sucked me into his immigrant story to an extra degree. When he describes the terrain back home, I thought back to my last visit, sitting in the back of my sister-in-law’s car watching the mountains go by as we drove from their town to the capital city.

Corchado relates the stories of his three friends — Primo, David and Ken — describing how they and their families came to be in the United States, what brought them here, how the early years went for them. He also does an important job for readers like me of informing and reminding from the U.S. side the historical and legal context of those migrations.

In short, he informs current debates by showing how often we’ve had the same discussions, but more than anything he gives such deep, connective views of the individual and family experiences as he explores a question than hangs over the entire book: Were all those journeys north, all those hard times in hard jobs in often not the most welcoming of circumstances worth it?

Corchado talks about having that specific conversation with his mother not long ago as they drove together:

“Did we do the right thing? my mother asked as she looked at the road ahead of us. To sacrifice everything that we knew — was it really worth it?

She echoed the same question we — David, Ken, Primo and I — had been asking for years. The question that consumed me from the moment I left El Paso all those years ago: Was the sacrifice worth the price?”

Like the way there is no single immigrant story, there is no single answer. His view, his mom’s view, that of his dad or a cousin or those who grew up on the other side of his town in Durango, they’re all different.

What I very much enjoyed about this book was the opportunity to see some things in a new light. For example, one thing my wife and I have talked about throughout our relationship is the basic question of where we would live and what we would have to do in order to do that. What would marriage mean for her status in the U.S.? Mine in Mexico? I remember a very simple, in retrospect kind of funny, and yet key question that came up as we drove across California the day we got engaged: “Wait, are we allowed to do this?”

So when Corchado discussed a push in the late 1990s for Mexicans to be allowed to hold dual citizenship, that was a time when I thought okay, I know the end result (yes) but I don’t know the history of that decision. I also didn’t think of a key nuance to that debate and its importance.

He specifically mentions a meeting at the Mexican presidential residence Los Pinos between then-President Zedillo and a group of U.S. elected officials and community leaders who had family ties to Mexico, including a state senator named Denise Moreno Ducheny.

“She knew Mexican immigrants were vulnerable. Their welfare status and the education of their children were now at stake in a state filled with hatred toward immigrants. They needed to vote. With dual nationality, Moreno told Zedillo, Mexican immigrants could more readily become U.S. citizens and still own property in Mexico, participate in Mexican elections and immerse themselves in U.S. politics.”

I read that section again just to make sure its impact was clear to me. That not only was it important for Mexicans to retain a connection to issues and representation back home by being able to hold dual citizenship, but that being dual citizens allowed them to no longer have to choose where they could have that representation. As dual citizens, they could advocate for themselves in both places, and thus were more likely to apply for U.S. citizenship and have access to those rights.

Going back to the personal nature you feel when you read a book, I have to mention two tiny examples that made me virtually point at the page and say, “Oh look!”

Corchado talks about his cousin Ruben who is working in Colorado and building a house back in Durango: “He was running out of money and joked that he might sell menudo and gorditas to finish the project.”

Roughly 20 minutes after I read that, my wife and I talked to her family in Durango. What were they about to eat? Menudo. Also gorditas are devine. My wife will tell you the ones from Durango are the best.

In another section, Corchado talks about the origins of a teaching stint at Arizona State University: “I was looking for Angela. We were there to interview for jobs at the school of journalism at ASU. Dean Chris Callahan wanted me to accept an endowed chair of the Borderlands Initiative.”

Callahan was the associate dean of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism when I was a University of Maryland graduate student. He taught our entry-level course designed to put everyone on the same page and refresh us on some basics. What I remember most is a fun assignment he would have us do that involved him reading a brief statement about something that happened in the real world (a car accident, fire, etc.) and then give us five or ten minutes to ask him questions as if here were the local authority. After that, we had to knock out a quick story using only that information.

I feel like I’m saying this for most of my reads this year, but this is a definite recommendation.