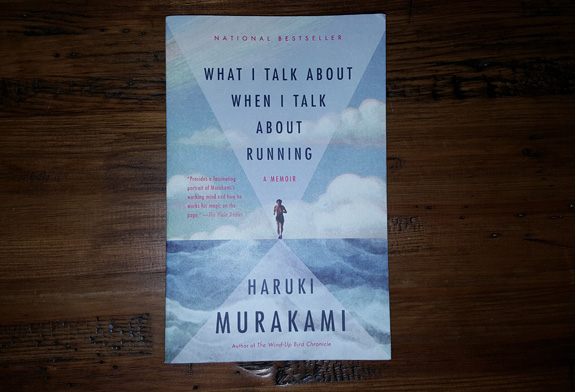

Before I started reading Haruki Murakami’s “What I Talk About When I Talk About Running,” I had already decided to run every day this month.

A few days into it, I turned 33, having been born in 1983. Murakami describes his own running streak, which he began at age 33 in 1982. My streak will not be decades-long like his, or years-long like my older brother’s current streak. I just wanted to do it for a month to shake up my running life.

Murakami is known for his stellar novels (I feel like I should use at least nine other adjectives there) while this is more of a memoir of his running life and how that relates to his writing. You do not have to be either a runner or a writer to enjoy it. A lot of what he has to say applies to anything that challenges you or you wish did.

He hits on something I think it so important in an age where it seems more than ever we care about what others think of us. At the end of the day, you answer to yourself.

“Maybe numbers of copies sold, awards won, and critics’ praise serve as outward standards for accomplishment in literature, but none of them really matter,” Marukami writes. “What’s crucial is whether your writing attains the standards you’ve set for yourself. Failure to reach that bar is not something you can easily explain away.”

The same goes for why you do the things you do. Inspiration strikes all of us in some way. We’re all busy and have lots of things we have to do, but somewhere there is a voice telling us about this other thing it would be cool to pursue.

“What I mean is, I didn’t start running because somebody asked me to become a runner. Just like I didn’t become a novelist because someone asked me to. One day, out of the blue, I wanted to write a novel. And one day, out of the blue, I started to run — simply because I wanted to.”

Reading this book I felt a real kinship with Murakami. I think there is a lot of similarity to our personalities.

“I’m the kind of person who likes to be by himself. To put a finer point on it, I’m the type of person who doesn’t find it painful to be alone. I find spending an hour or two every day running alone, not speaking to anyone, as well as four or five hours alone at my desk, to be neither difficult nor boring.”

It’s always refreshing to see other people say that.

He runs marathons and does triathlons so his training weeks include many more miles than mine. He also listens to music along the way, which is different from my preferred approach. But Murakami discusses the frequent question people ask of long-distance runners, wondering what it is we think about during all those hours out there. My usual answer is along the lines of, “Um, whatever pops up in my mind.” His is a little more eloquent.

“On cold days I guess I think a little about how cold it is. And about the heat on hot days. When I’m sad I think a little about sadness. When I’m happy I think a little about happiness. As I mentioned before, random memories come to me too.”

All of this doesn’t come close to scratching the surface of the good stuff in this book. I’ll close with a pretty solid piece of writing advice that I try to do on anything of length and really makes sense to me.

“I stop every day right at the point where I feel I can write more. Do that, and the next day’s work goes surprisingly smoothly. I think Ernest Hemingway did something like that. To keep on going, you have to keep up the rhythm. This is the important thing for long-term projects. Once you set the pace, the rest will follow.”