Knowledge is a weird thing. You can go your entire life completely oblivious to a fact, and then have it come up multiple times right in a row.

I began March with zero knowledge that Havana, Cuba, was once the home of a AAA baseball team. The Tampa Bay Rays played an exhibition game there last month, and related to that I did some stories about U.S.-Cuba baseball connections, including one that involved the Havana Sugar Kings.

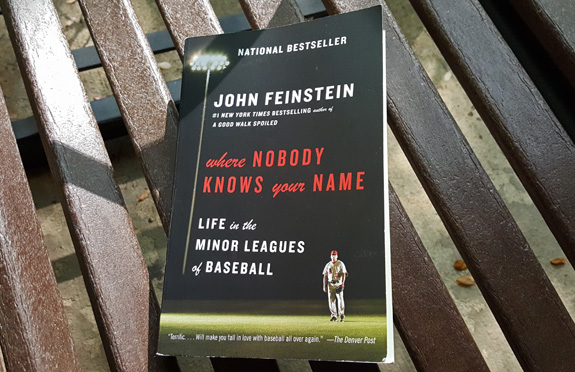

Fast-forward to April when I read John Feinstein’s “Where Nobody Knows Your Name” about what it’s like to be in the minor leagues. Even if I never researched that one Cuba baseball story, I still would have learned about the Havana connection when he described the International League.

“Once, the league truly was international: there were teams from Canada, Puerto Rico, and, for six years in the 1950s, Cuba.”

This book is full of those little nuggets, as well as countless interviews with a core set of minor league players, coaches and an umpire. Some are trying to just get to the major leagues, while others have spent much of their career there and hope they can get back one more time.

Like Brett Tomko, one of the people Feinstein follows throughout a season. In addition to getting to hear about his love of the game and all the things he’s fighting through to keep playing, there is an amazing nugget about Tomko’s family. His dad, Jerry, entered a contest in 1970 to name the Cleveland NBA team, and out of all the entries his choice of Cavaliers was selected.

For those who listen to Washington Nationals games on the radio and have ever wondered why the announcers take turns with play-by-play duties, Feinstein indirectly answers that. The Pawtucket Red Sox use that format, and Nats’ broadcaster Dave Jageler spent a year there before he was hired in DC.

I’m not the biggest overall fan of Feinstein, and sometimes have issues with his takes in Washington Post columns. But this book does a great job of showing the human side of baseball where everyone is trying, and as he and many of those interviewed point out, few have any desire to be in AAA.

That doesn’t stop people like Ron Johnson, manager of the Norfolk Tides from having a good attitude.

“‘The good news is we’ve got a great bus,’ Johnson said one night prior to a nine-hour trip to Gwinnett. ‘Nobody beats our bus.'”

The coaches are who really shine. They are put through extremely difficult tasks of trying to develop players and ostensibly win games, though nobody really cares about that part. At the same time, their rosters are constantly changing as the major league team decides what they need, and don’t. Time and again Feinstein describes a manager telling a guy he gets to go to the majors, and no matter the bind it creates in AAA, the sentiment is the same.

“‘Well, I’ve lost my two best outfielders in five days,’ [Indianapolis Indians manager Dean Treanor] said. He paused for a moment and smiled. ‘I couldn’t be happier.'”

Another thing I learned from this book: AAA managers don’t sit in the dugout.

“One reason that most Triple-A managers coach third base is to prepare themselves for possibly being a base coach in the major leagues,” Feinstein writes.

One of the managers who features extensively in the book is Charlie Montoyo, who at the time was the manager of the Durham Bulls. Well, that experience seems to have paid off, because today he is the third base coach for their major league team, Tampa Bay.

Not the most unbelievable sports book of all time, but as a baseball fan I really enjoyed it.